-

-

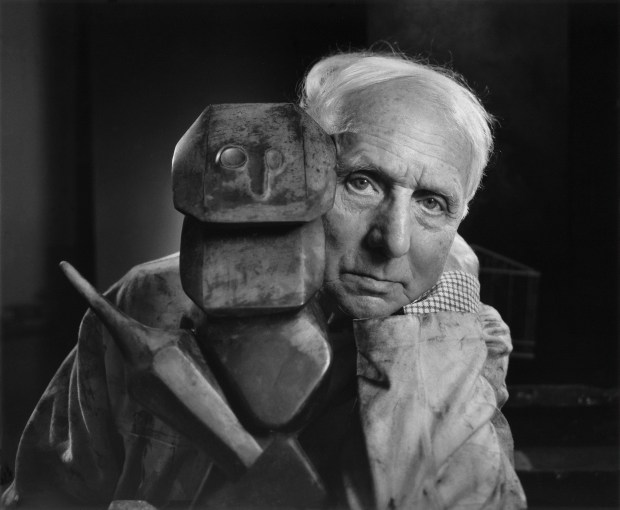

Kasmin is delighted to present Out of an Impasse: Bronze Sculptures by Max Ernst, 1934–1973, a new online exhibition on the gallery's website from May 31, 2023. Drawn from the collection of Dorothea Tanning, this presentation assembles six key examples of Ernst's impressive work in bronze, unearthing the whimsical yet rigorous methodology by which the preeminent figure of Dada and Surrealism approached his sculpture practice.

-

"Whenever I reach an impasse in my painting, which happens time and time again, sculpture always offers me a way out."

—Max Ernst -

The following text, unless otherwise noted, has been excerpted from Dr. Jürgen Pech in Max Ernst: Plastische Werke (Köln: DuMont Literatur und Kunst Verlag, 2005), translated in Allison Mosely's Max Ernst: Paramyths, Sculpture 1934–1967, exh. cat. (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2015).

At the end of May 1936, Max Ernst took part in the Exposition surréaliste d'objets, which was shown in the Charles Ratton Gallery, which actually specialized in African, Oceanic and American objects. André Breton had organized this survey exhibition and structured it through various classifications, which were also announced in an accompanying issue of the journal Cahiers d'Art: mathematical objects, natural objects, wild objects, found objects, irrational objects, readymade objects, interpreted objects, incorporated objects, and moveable objects. André Breton assigned Max Ernst's works to the terms "natural objects," "found objects," and "surrealistic objects." Max Ernst was represented in the exhibition with four works. In addition to Habakuk, which was presented in a showcase together with mathematical wire models, a Kachina doll and objects by Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso, his wooden object Objet mobile recommandé aux familles and the plaster sculpture La belle allemande, and finally Les asperges de la lune could be seen in the garden.

The found object was a stone that a friend, the collector and artist Roland Penrose, had given to Max Ernst after a trip to Egypt: "One of the simplest and most lasting souvenirs I brought back with me was a small stone that I had found. It was sand-polished, spherical like a large cherry pit, and rimmed with horns that corresponded to the shape of the waxing moon…On my return to Paris, Max Ernst picked it up as an important Surrealist object, preserved it in a jewel box lined with velvet or exhibited it together with his paintings as an exceptional treasure." When the found object was shown again at the end of 1937 at the Surrealist Objects & Poems exhibition in London, it was given the name Sphinx Eye in the catalogue. The association with the puzzler of Greek mythology, which goes back to the mythical animal with a human head and lion's body, summarizes the discovery site of the round polished stone and the eye as the central theme in Max Ernst's work. -

-

-

For his figure Habakuk, into which plaster copies of the stone were incorporated, Max Ernst stacked three casts of a flower pot on top of each other so that the smaller and the larger radii are on top of each other. He moved the upper cast backwards at a slight angle, matched the protruding material shape to the underlying, load-bearing curve and modeled the gap between the two pot shapes to the mouth opening. In the lower pot he added a fourth cast, which can only be seen as a narrow section and forms the base of the figure. The stepped structure largely corresponds to Oedipe I; there the figure is also placed off-center on a high, circular base. In the first version shown by Charles Ratton, the place next to it was occupied by a pipe, which is to be understood as a reminiscence of the guild pipe from the first Cologne Dada exhibition of 1919, and by a cast of the Penrose stone.

-

Max Ernst, The Barbarians, 1937, oil on cardboard, 9 ½ × 13 inches, 24.1 x 33 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, 1998. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

-

(Left) Max Ernst in Great River, Long Island, Summer 1944. Courtesy of Dr. Jürgen Pech, Bonn. (Right) Max Ernst, The Duck of Doubt with Vermouth Lips (Le canard du doute aux levres de vermouth), 1948, oil on canvas, 30 × 20 inches, 76.2 × 50.8 cm. The Menil Collection, Houston. Bequest of Marcia Simon Weisman.

(Left) Max Ernst in Great River, Long Island, Summer 1944. Courtesy of Dr. Jürgen Pech, Bonn. (Right) Max Ernst, The Duck of Doubt with Vermouth Lips (Le canard du doute aux levres de vermouth), 1948, oil on canvas, 30 × 20 inches, 76.2 × 50.8 cm. The Menil Collection, Houston. Bequest of Marcia Simon Weisman. -

Plaster components for sculptures at Max Ernst's studio, Paris, 1935. Courtesy of Dr. Jürgen Pech, Bonn.

Plaster components for sculptures at Max Ernst's studio, Paris, 1935. Courtesy of Dr. Jürgen Pech, Bonn. -

"Ernst's sculptures are neither truly abstract nor obviously figurative in nature, but often an enigmatic combination of both." —Michele Wijegoonaratna

-

-

-

Max Ernst, Etes-vous Niniche?, 1961, wax crayon on paper, 21 ⅞ × 17 ¼ inches, 55 x 44 cm. Private Collection. Courtesy of Dr. Jürgen Pech, Bonn.

-

"The humor also plays out in the gentlest of ways with works such as Dream Rose, a fond and whimsical rendering of his favorite Tibetan dog." —Michele Wijegoonaratna

-

-

The little creature known as Dream Rose has found its place. Its four paws—inspired by shell shapes, which Ernst eventually cast in bronze—take up the entire circular base, although the feet jut out slightly from the rounded edges. The body ends in an equally round collar, out of which rises a truncated cone. Two years later, Ernst used the circular shape and truncated cone to make the dress for his Woman from Tours. The footprint for La Tourangelle, however, is employed as the face for Dream Rose. The creature sticks out its tongue at the viewer, and its semicircular eyes are protected by a surrounding indentation. Curiosity and fear are both shown to advantage.

"Dream Rose" was the name that Ernst and Dorothea Tanning gave to one of their dogs. Over time, the dog became an emblematic animal in Tanning's work; in her memoirs, Tanning mentions the first dog, a Lhasa Apso terrier named Kachina, in her description of Ernst's move into her apartment: "A glory of objects and pictures expanding my rooms, making other worlds out of my walls. And as if that were not enough, the Hopi idols, Northwest coast wolf mask, New Guinea shields. There was a totem pole that just touched the ceiling. A little dog named Kachina came with him and sat trembling…between the two front windows.” -

-

-

In addition to disc sculptures such as Dans les rues d'Athènes or Un chinois égaré, three pole sculptures were also created in the years around 1960, whose genealogy dates back a quarter of a century to Les asperges de la lune of 1935. This group includes the two works Sous les ponts de Paris, a monument to a frog designed in a mocking Dada manner, and mes-sœurs, which is most closely related to the original pair from the 1930s with its division into two parts. Both are overtopped in height by the sculpture Le génie de la Bastille, which with over three meters directs the view upwards.

"With Le génie de la Bastille, Ernst set a bird monument to the pursuit of freedom of the French Revolution."

In Le génie de la Bastille, the supporting and presenting form of the pole has grown into a column of enormous length. The slight flute of the 1935 prototype has now given way to a strong structuring. Max Ernst achieved the coarse, irregular grid by pouring out a fish trap with plaster. A corresponding mold, taken from everyday reality, can be discovered in a photograph of the studio in Huismes, where it leans against the wall on the left in the background. After the plaster had dried, Max Ernst cut the wickerwork and placed four casts on top of each other for the column shaft. He crowned the top with a bird figure with wide-spread wings. Like the column, this emblem of the artist is also composed of individual parts, which are added together and constructed completely symmetrically. The smooth surface of the animal emphasizes its contrast and independence. The emblem animal consists of three basic forms: wing, half of the body, and head, which at the same time functions as a leg section. The basic forms were each created twice and support the balanced effect in their repeated or mirrored arrangement. In the following years Ernst equipped further casts of the central body part of the bird with eyes in order to create the heads of the frogs of Sous les ponts de Paris and Deux assistants through this transformation.

When the bronze casting of Le génie de la Bastille was placed in the garden of Huismes, an inverted Corinthian capital served as the base. At the end of the 1960s Ernst took up the combination of stone and bronze again for the design of the fountain at Amboise. The end of a Greek column here becomes the carrier of a column and acquires a meaning in terms of content: a new free spirit emerges from a fragment of the past. With Le génie de la Bastille, Ernst set a bird monument to the pursuit of freedom of the French Revolution. The title recalls the state prison in Paris, notorious since Richelieu, which had been stormed and destroyed at the beginning of the revolution in 1789 as a sign of royal tyranny. To commemorate the July Revolution of 1830, the July Column was erected on Bastille Square, bearing the Roman genius of freedom—a male figure that is also winged.

-

-

-

-

With Chéri Bibi, Ernst took up the design form of the disc sculptures that could be found in his sculptural work since the 1930s. The formal series began with the pair Oiseau-téte and La belle allemande, which were created in Paris in 1934–35, was continued by him in 1944 in Long Island with Un ami empresséand Jeune femme en forme de fleur, in which he incorporated the possibility of a deep stratification into the room, and he finally varied it again in Dans les rues d'Athènes and Un chinois égaré from 1960, by applying small, fully plastic figures to the presentation tableaux.

The compositional scheme of body surfaces with additively applied individual elements is adopted directly, whereby this time the clear and symmetrical arrangement of simple surfaces, an upright rectangular plate and a circular disc creates the impression of a harmonious balance. The name Chéri Bibi goes back to the hero of a novel series begun in 1911 by Gaston Leroux, author of the work Phantom of the Opera. The main character of the series is a good-natured colossus who had repeatedly broken out of prison. Pursued by a merciless fate and forced to commit crimes, his motto was: "Disastrous!"

In Ernst's bronze the location of the figure is not certain. The pedestal consists of two different sized hemispheres set against each other, whereby the fatal situation of the hero is abstractly but clearly implemented. The rectangle of the body frames the circular silhouette of the head so massively and completely that the impression of a massive corporeality is created. The face itself is not sculpturally formed, but is stamped into the plate-shaped surface of the head. At the same time, the outstretched tongue expresses the hero's carefree composure. Ernst's sculpture unites the exciting contrast of the literary model, the uncertain circumstances of life and the nevertheless self-confident attitude of the fictitious character. -

-

-

"Ernst's sculpture unites the exciting contrast of the literary model, the uncertain circumstances of life and the nevertheless self-confident attitude of the fictitious character."

—Dr. Jürgen Pech -

Works

-

About the Artist

-

Explore

-

vanessa german: GUMBALL—there is absolutely no space between body and soul

April 3 – May 10, 2025 509 West 27th Street, New York, 514 West 28th Street, New YorkKasmin presents its second solo exhibition of new work by artist vanessa german, which debuts related bodies of sculpture across two of the gallery’s spaces in New York. The exhibition deepens german’s singular approach to sculpture as a spiritual practice with the power to transform lived experience. Both series comprise mineral crystals, beads, porcelain, wood, paint and the energy that these objects bring to life to form monumental heads and figures in the act of falling. Together, each body of work envisions the transformation of consciousness necessary to imagine a new world. -

Theodora Allen: Oak

May 7 – July 25, 2025 297 Tenth Avenue, New YorkAllen’s atmospheric oil paintings on linen depict natural phenomena and symbols chosen for their enduring presence in human history and culture, often drawing from mythology and medieval imagery. From hearts and infinity loops to rainbows and locusts, these subjects serve to underscore nature’s propensity for renewal following destruction. Branches of an oak tree, a powerful symbol of wisdom, strength and endurance, reappear. Through compositional devices, such as gates, windows, and architectural niches, Allen's illusionistic spaces create a dynamic interplay between inclusion and exclusion. Her scenes emerge as ruins burgeoning with life, offering glimpses into a realm where the natural world and the metaphysical entwine.

-